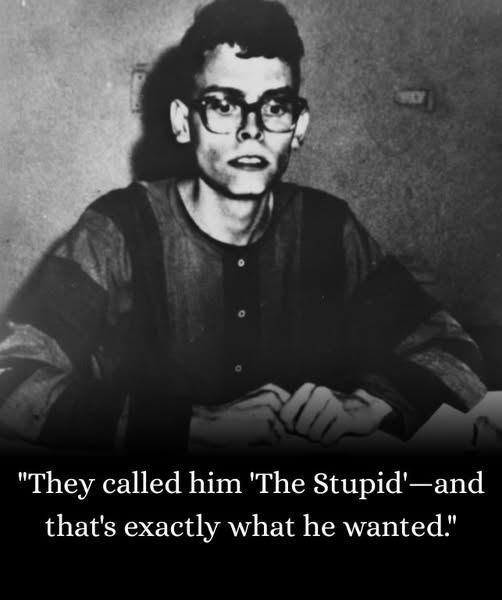

In the world of war, where physical strength and combat prowess often dominate, it’s easy to forget that some of the most powerful strategies come from the mind. One of the most remarkable stories of this mind-over-matter philosophy is that of Navy sailor Douglas Hegdahl, who, while being held captive during the Vietnam War, used the power of being underestimated to save the lives of 256 prisoners of war.

It’s a story of intelligence, cleverness, and silent rebellion, and it reminds us that sometimes, the greatest strength lies in letting others think they’ve won. This is the tale of how Hegdahl, labelled “The Stupid,” became one of the war’s most valuable intelligence assets.

Chapter 1: The Stupid Sailor – A Simple Strategy

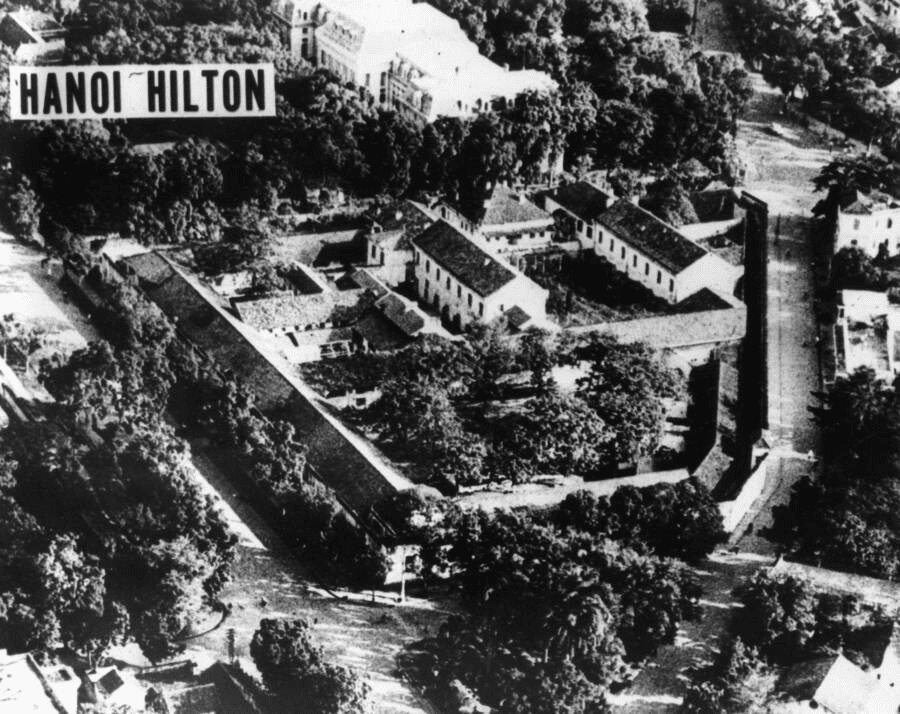

The Vietnam War was filled with stories of bravery and heroism, but none perhaps as unique as that of Douglas Hegdahl. Captured by the North Vietnamese forces during a routine mission in the early 1960s, Hegdahl found himself thrown into the notorious Hanoi Hilton, a prison camp where physical and psychological torture was the norm.

Hegdahl was just 19 years old when he was captured, and he found himself alone in a strange and hostile environment. The North Vietnamese forces, notorious for their cruelty, assumed Hegdahl would be an easy prisoner. Young, naïve, and seemingly harmless, he was quickly thrown into the prison with little more than the clothes on his back. His captors decided that they had a “dumb” prisoner on their hands, a sailor too weak and innocent to pose any serious threat.

It’s a terrifying position to be in. But for Hegdahl, it was an opportunity. He knew that any attempt to resist would only draw attention to himself and possibly lead to even harsher treatment. Instead, he made a bold choice that would eventually save the lives of hundreds. He would play the fool.

Hegdahl adopted the persona of “The Stupid,” acting confused, clumsy, and docile, all the while under the watchful eyes of his captors. His aim was simple: make them believe that he wasn’t worth their time or attention. And so, his days became a performance—he stuttered through conversations, feigned confusion, and allowed himself to be ridiculed.

And it worked. The Vietnamese guards laughed at him. They thought he was too simple to be of any value. They allowed him to wander the camp with little supervision, seeing him as no threat at all. What they didn’t know was that they had just made a catastrophic mistake.

Chapter 2: Playing Dumb, Hegdahl’s Silent Rebellion

While his captors mocked him, Hegdahl was busy observing every detail around him. He took note of the guards’ routines, the vulnerabilities in their operations, and, most importantly, the prisoners who shared his fate. While he feigned ignorance, Hegdahl quietly began sabotaging the enemy’s efforts.

One of the first things he noticed was the trucks used by the North Vietnamese. They were essential for transporting supplies and troops, but they weren’t always in top condition. Hegdahl, taking advantage of his perceived incompetence, began sneaking around and sabotaging them. He would pour dirt into the fuel tanks, rendering the trucks useless and causing delays in the enemy’s operations. A seemingly small act, but it had a lasting impact. Hegdahl’s clever sabotage created a ripple effect, disrupting the enemy’s plans without them ever suspecting the truth.

But Hegdahl’s greatest act of defiance was invisible. The guards had no idea that while they thought they were dealing with a “stupid” prisoner, Hegdahl was busy memorizing something far more important: the names, faces, and details of his fellow prisoners.

Every day, he observed the men around him. He watched their interactions, listened to their stories, and carefully committed every piece of information to memory. He knew the enemy deliberately kept details about the prisoners hidden from the outside world, and he realized that if he could remember everything, he could make sure no one would be forgotten.

Hegdahl memorized 256 names of fellow prisoners—256 faces, 256 families who deserved to know their loved ones were alive. It wasn’t just about remembering names; it was about preserving the humanity of each prisoner. The simple act of memorizing these details would prove to be one of the most valuable intelligence assets of the war.

But how did Hegdahl manage to remember so much? The solution came in the form of an unlikely mnemonic device: the children’s song, “Old MacDonald Had a Farm.” Hegdahl set each prisoner’s details to the rhythm of the song, silently singing it in his head day after day, making it easier for him to recall their names, capture dates, and other vital information.

Chapter 3: A Propaganda Stunt Gone Wrong

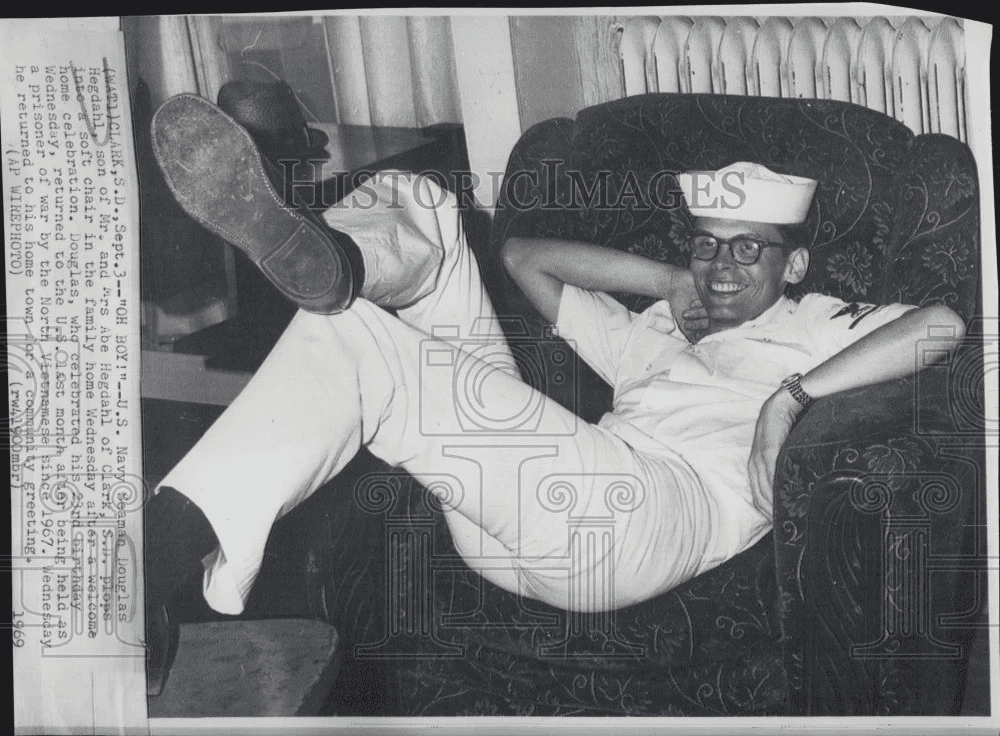

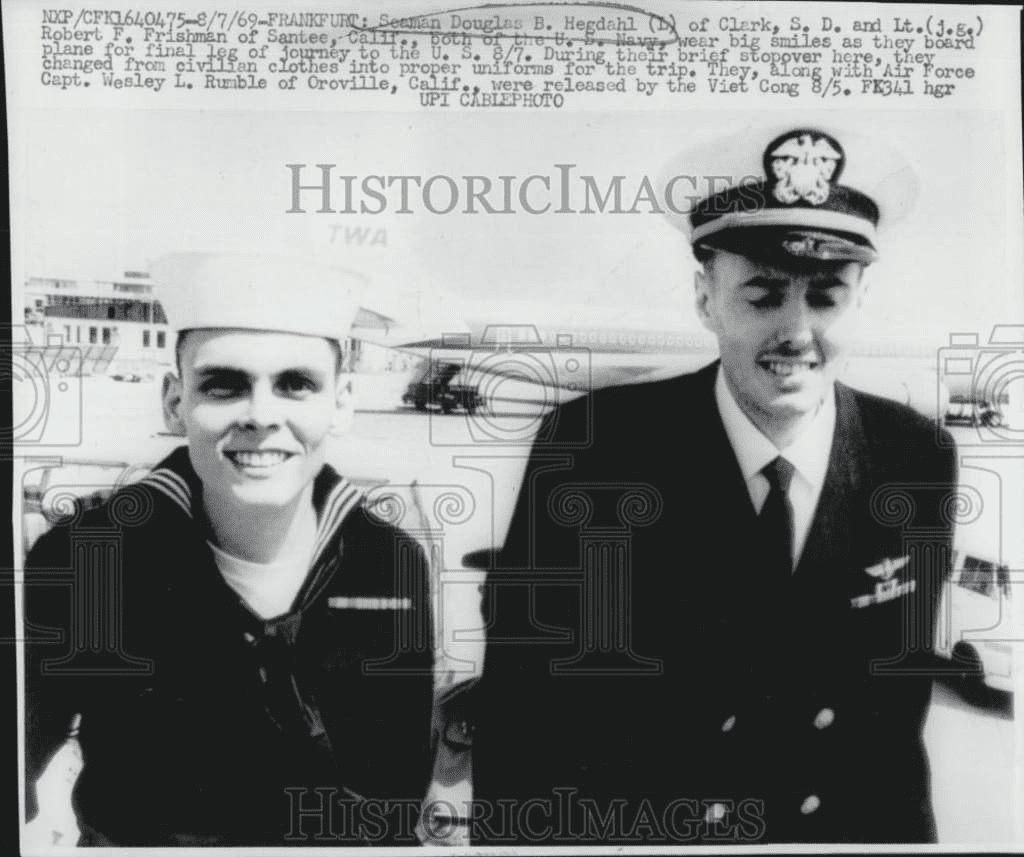

In 1969, after years of brutal captivity, Hegdahl was finally released. The North Vietnamese, eager to use him as part of a propaganda stunt, believed they were freeing a harmless fool—an unintelligent, harmless prisoner who had been no threat during his captivity. They were so confident in their assessment of him that they allowed him to leave without suspicion.

But they couldn’t have been more wrong. The moment Hegdahl returned to American soil, he became one of the most valuable intelligence assets the U.S. had during the war.

The North Vietnamese had thought that they were releasing a man with no intelligence, but in reality, they had just handed over one of the most carefully crafted intelligence operations of the war. Hegdahl immediately delivered every piece of information he had gathered: the names of 256 prisoners, their capture dates, and the conditions under which they had been held.

Thanks to Hegdahl’s extraordinary memory and dedication, the U.S. government now had detailed information about the prisoners still held in North Vietnamese custody. His efforts helped ensure that these 256 men would not be forgotten, and it gave hope to the families who feared their loved ones had disappeared forever.

Chapter 4: The True Power of Intelligence

Hegdahl’s story is a perfect example of how underestimated individuals can make the biggest impact. By playing dumb, Hegdahl not only saved his own life but also became the key to freeing hundreds of others. It was his courage, intelligence, and quiet defiance that made him a true hero.

The lesson here is clear: Sometimes, strength isn’t measured by physical might but by mental resilience and the courage to outwit those who underestimate you. In war, as in life, the greatest weapon isn’t always a sword—it’s the ability to outthink and outlast your enemies.

Hegdahl’s quiet rebellion serves as a reminder that intelligence comes in many forms, and sometimes the most valuable weapon isn’t what people expect. It’s the courage to play the long game, to let others underestimate you, and to use your mind to create change in ways no one could ever predict.

Chapter 5: The Legacy of Douglas Hegdahl

Douglas Hegdahl’s story is one of profound bravery and extraordinary intelligence. While the world may remember his capture as a mere footnote in the Vietnam War, his actions in the Hanoi Hilton saved hundreds of lives and ensured that the names of 256 prisoners would be remembered.

His legacy is a testament to the power of intellect, humility, and the ability to think outside the box. It also serves as a powerful reminder that sometimes, it’s not strength that wins wars—it’s the quiet, clever rebellion that catches the enemy off guard and changes the course of history.

Chapter 6: The Psychology of Underestimation—Why It Works

The story of Douglas Hegdahl doesn’t just highlight the power of playing the fool—it sheds light on a fascinating psychological phenomenon: underestimation. Hegdahl’s captors saw him as weak, naïve, and unthreatening, and this perception influenced their treatment of him. It’s not just about the physical strength or intelligence of the individual; it’s also about how perception shapes actions and decisions.

Underestimation is a powerful tool in warfare, and history has shown that it can be one of the most dangerous mistakes an enemy can make. In the case of Hegdahl, his captors thought that they were dealing with an unimportant prisoner who posed no threat. They had fallen into the trap of overestimating their control and underestimating the potential of those they held captive.

The psychology behind this is fascinating: when someone is underestimated, they are often given more freedom, less scrutiny, and the opportunity to act without raising suspicion. Hegdahl used this gap in his favor. By performing the role of a “simpleton,” he gained the freedom to observe, collect intelligence, and sabotage the enemy’s operations without the interference that other prisoners might have faced.

In many cases, history has shown that those who are underestimated are the ones who end up having the most significant impact. Their enemies are blind to their potential, which gives them the upper hand in covert operations. Hegdahl’s ability to manipulate this perception was one of his greatest assets.

Chapter 7: The Role of Memory in Warfare—How Hegdahl’s Strategy Defied the Odds

One of the most remarkable aspects of Hegdahl’s story is his ability to memorize the names and details of 256 prisoners. This wasn’t a simple task; it required extraordinary mental discipline and a deep understanding of how the brain can be trained to store and recall vast amounts of information.

Hegdahl’s decision to use a mnemonic device—“Old MacDonald Had a Farm”—was not just a creative solution to his predicament; it was a demonstration of how memory can become a weapon. The song’s familiar rhythm and structure allowed Hegdahl to internalize the information in a way that made it easy to recall under pressure. In many ways, his use of memory to track the identities of fellow prisoners was a form of mental warfare.

The connection between memory and survival is profound. In times of crisis, memory becomes a way to hold onto one’s humanity, to preserve dignity in the face of dehumanization, and to fight back against those who attempt to strip away everything you hold dear. Hegdahl didn’t just survive in the Hanoi Hilton—he weaponized his memory.

Beyond the practical aspect of remembering prisoners’ details, his actions also highlight an essential truth of warfare: information is power. In a war where physical strength can only take you so far, knowledge—especially knowledge that is hidden from the enemy—becomes one of the most valuable assets a person can have. Hegdahl’s mental discipline not only saved lives but also gave hope to those who had lost all faith.

Chapter 8: The Cost of War—What Hegdahl’s Story Teaches Us About Human Resilience

Though Hegdahl’s story is one of triumph, it’s important to recognize the cost of war and the human toll it takes. Hegdahl’s actions, while heroic, were born out of a situation where he had no choice but to survive. His ability to adapt, outwit his captors, and remember the details of his fellow prisoners speaks to an extraordinary level of resilience. But behind his intelligence and bravery, there is a deeper, more painful truth: the immense psychological toll of captivity.

During his time in the Hanoi Hilton, Hegdahl endured both physical and psychological torment. The constant threat of violence, the isolation, and the psychological manipulation would have broken many people. Yet, Hegdahl’s decision to “play dumb” was not just a tactical move—it was also a survival strategy that protected his mental health.

The power of resilience in wartime cannot be overstated. Hegdahl’s story shows that even in the most hopeless of situations, the human spirit can survive and even thrive. He found a way to navigate the brutal environment of the Hanoi Hilton by refusing to let it break him. His strength came not just from his body or his mind, but from his ability to maintain his sense of self—his belief that he could make a difference.

This speaks to something deeply human: hope. It’s hope that drives individuals to keep going even when the odds are stacked against them. And while Hegdahl’s victory was a product of intelligence and strategy, it was also a story about the will to survive and protect others, no matter the cost.